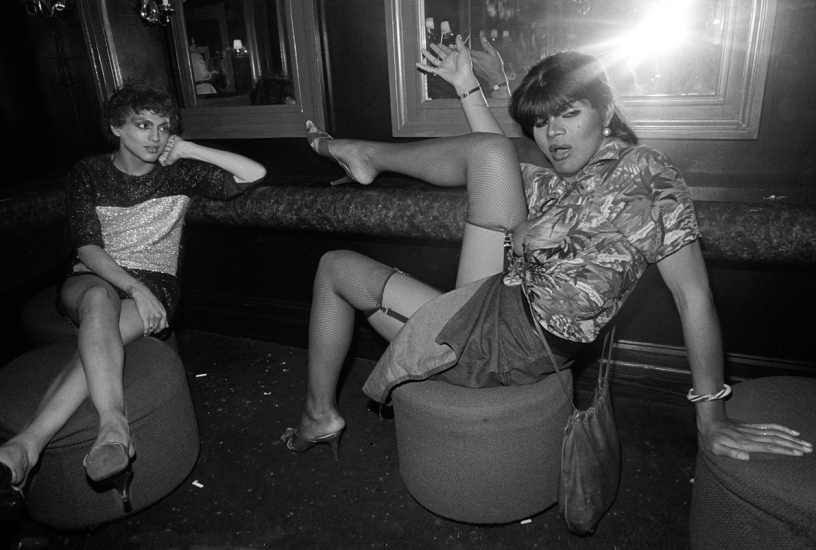

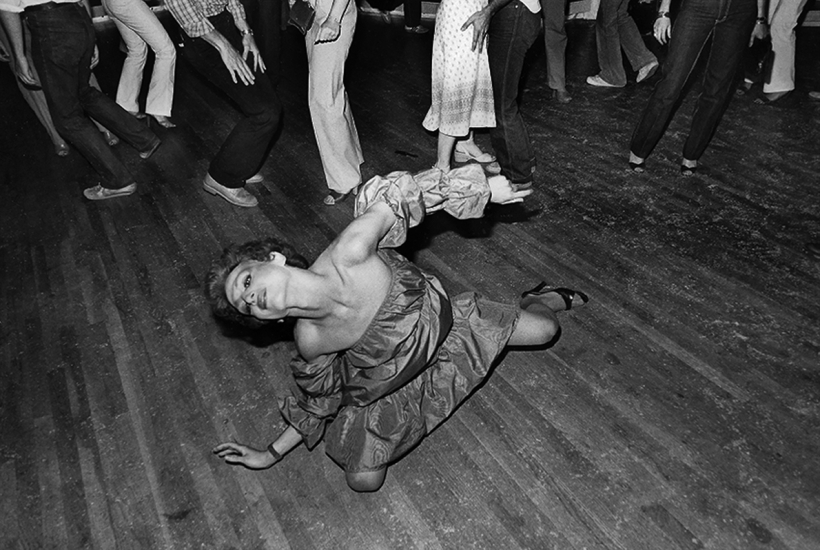

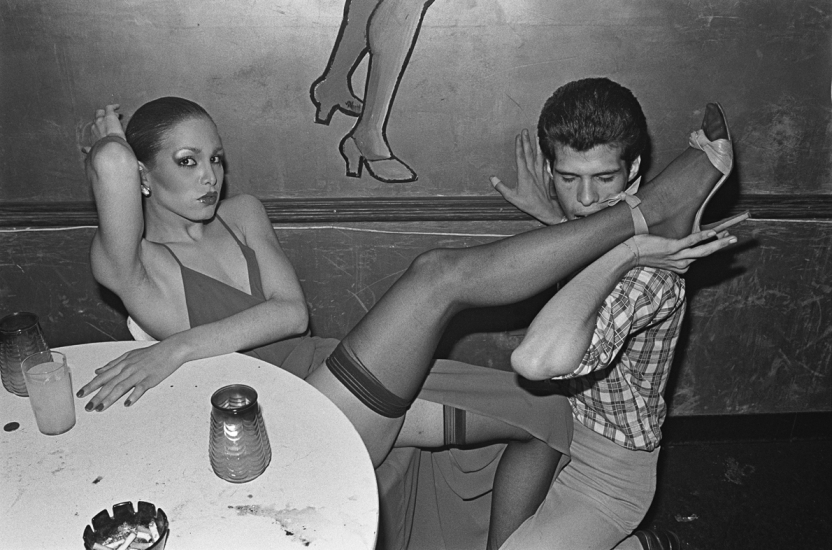

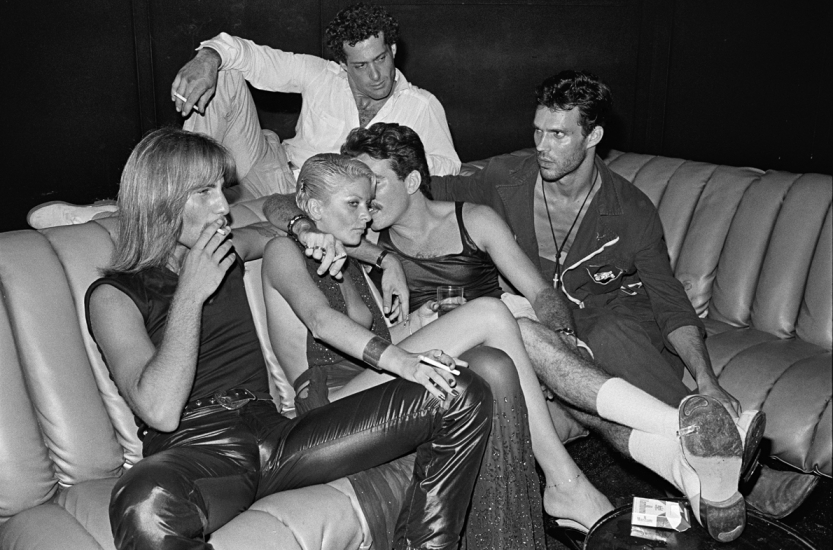

New York of the 1970s, a city in crisis. While the metropolis is heading towards financial ruin, a wild nightlife is raging in the clubs of the Big Apple. Freedom, parties, excess, tolerance— here the entire scene is celebrating the unspoken laws of equality, acceptance, and exuberance. During this time, photographer Bill Bernstein was a regular frequenter ofthe city’s nightclubs, taking photographs at the legendary Studio 54, as well as the Paradise Garage, the Mudd Club, and Empire Roller Disco. Bernstein’s images tell ofa short-lived but intensive, carefree moment in time. More than anything, what makes his photographs unique is the view they provide of the action on the sidelines. Here the focus is not on celebrities but the multitude of various characters that shaped New York’s nightlife during these years and filled up the dance floors. Following a showing ofBernstein’s photographs from 1977–79 last year at the Museum ofSex in New York, they are being presented for the first time in Berlin at the Galerie für Moderne Fotografie.

Anneli Botz: Your images from the series The Bill Berstein Photographs—NYC 1977 to 1979 feature the New York party scene of the late seventies. Now, over thirty-five years later, you are showing these photographs in Berlin. Why here?

Bill Bernstein: When I was first hanging out in the New York club scene at night, I photographed a couple whose look reminded me of Berlin in the twenties, like in the film Cabaret. A man and a woman, both in tailcoats, with distinctive make-up, androgynous and non- conformist. For me they embodied the unrestricted nightlife culture and excessive life of the wild twenties in Berlin. And that, in turn, seemed to me to parallel what was happening in New York at the time. Since then, this connection to Berlin has existed for me.

AB: What was New York City like then?

BB: New York City was in a state ofcrisis, on the brink offinancial ruin, with a high crime rate. Trash piled up on the streets since the garbage collectors were permanently on strike. There were not enough policemen and not enough firefighters. Something was always on fire somewhere and graffiti covered the walls on the streets. But at the same time the city was a cheap place to live, a lot of artists lived here, the concentration of creativity was ever-present. This creative development stood opposite to the financial crash. Added to this was the empowering of important marginalized groups; the LGTB, women’s, and African American civil rights movements really gained in stature for the first time. While the city was outwardly in recession, people in the clubs were celebrating excessiveness, one another, and life. It was as if the long-suppressed subcultures were performing their victory dance here. The music that came out during this time was very inspiring and had nothing to do with a negative protest attitude.

AB: So it was one giant party. How was it for you to take pictures in the clubs?

BB: The hardest thing was getting into the clubs, for example Studio 54. But after awhile they knew me there. At that time there weren’t very many photographers out at night—cameras and flashes were more ofa rarity. I was often the only one with a camera and they just accepted me like that. Also, I never met anyone who told me no when I asked if I could take their photo. AB: What was different about the various clubs?

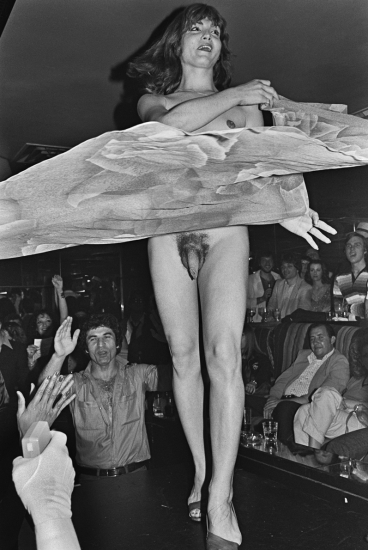

BB: If you’re going on the extremes, on one side you’ve got Studio 54, as a professional high- end club, with a mix of celebrities and beautiful New Yorkers, LGBTS, and a lot of posers. A lot of them went there to be seen, to take drugs, and have sex. Being there was also about boosting your status since it was the most famous club in those years. Then there was GG’s Barnum Room, which actually started out as a transgender disco, but quickly became a hit with a wider audience. I loved this club. There was something circus-like about it, with a net hanging over the dance floor and transsexual performers, the so-called Disco Bats, swinging on trapezes.

AB: What was the name of the club where DJ Larry Levan spun records?

BB: That was the Paradise Garage on King Street—a disco located in a former garage that was an important gathering place for the black gay community in particular. A lot of people would go there because of Larry Levan and his music, mainly because people went to the Paradise Garage to dance until the early morning hours. Since the owners had no license to serve alcohol, there were only juices and fruit. The public brought their own drugs, mostly poppers, cocaine, or marijuana.

AB: What was the musical antipode to disco music back then?

BB: In Tribeca, I took a lot of photographs at the Mudd Club, which was actually a kind of anti- nightclub. Mainly New Wave and punk rock was played there, it was almost New York’s answer to British punk, although here it was more about the pose and the look than an anti- materialistic attitude. Nonetheless, everyone at the Mudd Club hated everything that had to do with Studio 54.

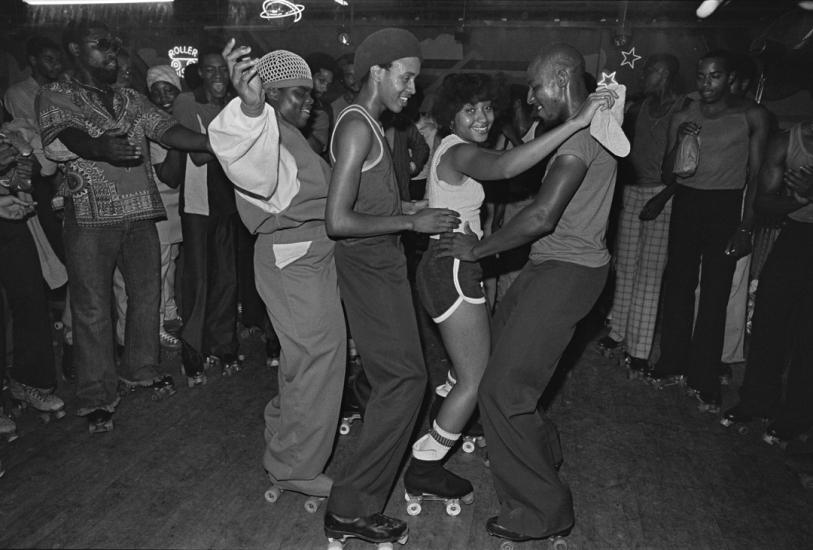

AB: Some of your images are from the roller disco.

BB: In New York there were a lot ofreally good roller skaters who used to party and perform their tricks together. Mostly I was at the Brooklyn Empire Roller Disco a lot, where African- Americans in particular came to skate. There was a mood of friendly competition, the air was sweaty, the audience full of energy.

AB: Did you feel a part ofthe scene then, or more like a kind ofobserver?

BB: I was a journalist, observing, taking notes. I still felt accepted. What attracted me the first night was just a feeling of being free to express yourself the way you wanted. There was a kind of belongingness I’d never encountered before, nowhere else.

AB: And you’re from the Woodstock generation.

BB: Exactly. I thought we were very tolerant. But in fact, my generation was heavily influenced by doctrine. You always had to be anti-everything. Anti-establishment, anti-Vietnam, anti-war, anti-materialism, anti-short hair. The scene of the late seventies in New York City was open- minded in a totally different way. Everything unfolded in the brief period of time after Stonewall, i.e. in the clashes between the police and homo and transsexuals, and before the AIDS epidemic. It was about equality and sex, for a short time everything was possible.

AB: What made a photo special for you then?

BB: As a photographer you’re always looking out for the unusual. So do I. When I went to Studio 54 for the first time, there was a long line of paparazzi who were only interested in somehow shooting a star. Every movement was documented there. But I wasn’t into this wrestling match with the other photographers at all, I wasn’t interested in photographing how Andy Warhol was sitting on the couch with Mick Jagger. If anything, as a portrait photographer, I wanted to have Mick Jagger sitting in my studio, with real light and decent equipment, interacting with him personally. In the clubs, I was much more interested in the other people who, in turn, wanted to celebrate the celebrities because they brought the vibe with them. So I only focused on what was going on alongside the stars and in particular in the underground clubs.

AB: Which makes your photographs fundamentally different from other images from this time. Do you look back nostalgically on those years from 1977–79, or you don’t miss it?

BB: If hadn’t been there, I would probably regret it. But I don’t want to go back; I think our culture has evolved in extremely significant ways since then. Because even ifgay, heterosexual, and transsexuals were happily dancing side by side on the dance floor, and women and blacks weren’t discriminated against there, this equality ended pretty quickly as soon as the clubs locked their doors. Discrimination and racism still ruled the streets; equal rights were never part of the equation then. I think, in general, the world is a better place today, even though there seem to be current movements trying to ratchet everything back a bit, but that will pass. I believe people really want a world of belongingness, tolerance, and acceptance.

When co-curator Arman Naféei encountered the photographs of Bill Bernstein at the Museum of Sex in New York in 2018, he quickly realized their particular value as testaments to a particular period in time.

Together with gallery owner Kirsten Landwehr, who has been acquainted with the work ofthe American photographer for several years, he decided to honor Bernstein’s wish for an exhibition in Berlin. Bernstein’s series The Bill Amber Photographs—NYC 1977 to 1979 will be on view at the Galerie für Moderne Fotografie in Berlin-Mitte starting September 27. The opening will be held on September 26 at the Galerie für Moderne Fotografie and followed by a reception at the 25hours Hotel Bikini Berlin of the 25hours Hotels Group, which has already included thirty of Bernstein’s works in their collection. On this evening, at the legendary Monkey Bar, various DJs, including Nicky Siano and Arman Nafeei, will pay tribute to the photographer by bringing disco fever back to life with new and old hits.

Text: Anneli Botz

Anneli Botz: Your images from the series The Bill Berstein Photographs—NYC 1977 to 1979 feature the New York party scene of the late seventies. Now, over thirty-five years later, you are showing these photographs in Berlin. Why here?

Bill Bernstein: When I was first hanging out in the New York club scene at night, I photographed a couple whose look reminded me of Berlin in the twenties, like in the film Cabaret. A man and a woman, both in tailcoats, with distinctive make-up, androgynous and non- conformist. For me they embodied the unrestricted nightlife culture and excessive life of the wild twenties in Berlin. And that, in turn, seemed to me to parallel what was happening in New York at the time. Since then, this connection to Berlin has existed for me.

AB: What was New York City like then?

BB: New York City was in a state ofcrisis, on the brink offinancial ruin, with a high crime rate. Trash piled up on the streets since the garbage collectors were permanently on strike. There were not enough policemen and not enough firefighters. Something was always on fire somewhere and graffiti covered the walls on the streets. But at the same time the city was a cheap place to live, a lot of artists lived here, the concentration of creativity was ever-present. This creative development stood opposite to the financial crash. Added to this was the empowering of important marginalized groups; the LGTB, women’s, and African American civil rights movements really gained in stature for the first time. While the city was outwardly in recession, people in the clubs were celebrating excessiveness, one another, and life. It was as if the long-suppressed subcultures were performing their victory dance here. The music that came out during this time was very inspiring and had nothing to do with a negative protest attitude.

AB: So it was one giant party. How was it for you to take pictures in the clubs?

BB: The hardest thing was getting into the clubs, for example Studio 54. But after awhile they knew me there. At that time there weren’t very many photographers out at night—cameras and flashes were more ofa rarity. I was often the only one with a camera and they just accepted me like that. Also, I never met anyone who told me no when I asked if I could take their photo. AB: What was different about the various clubs?

BB: If you’re going on the extremes, on one side you’ve got Studio 54, as a professional high- end club, with a mix of celebrities and beautiful New Yorkers, LGBTS, and a lot of posers. A lot of them went there to be seen, to take drugs, and have sex. Being there was also about boosting your status since it was the most famous club in those years. Then there was GG’s Barnum Room, which actually started out as a transgender disco, but quickly became a hit with a wider audience. I loved this club. There was something circus-like about it, with a net hanging over the dance floor and transsexual performers, the so-called Disco Bats, swinging on trapezes.

AB: What was the name of the club where DJ Larry Levan spun records?

BB: That was the Paradise Garage on King Street—a disco located in a former garage that was an important gathering place for the black gay community in particular. A lot of people would go there because of Larry Levan and his music, mainly because people went to the Paradise Garage to dance until the early morning hours. Since the owners had no license to serve alcohol, there were only juices and fruit. The public brought their own drugs, mostly poppers, cocaine, or marijuana.

AB: What was the musical antipode to disco music back then?

BB: In Tribeca, I took a lot of photographs at the Mudd Club, which was actually a kind of anti- nightclub. Mainly New Wave and punk rock was played there, it was almost New York’s answer to British punk, although here it was more about the pose and the look than an anti- materialistic attitude. Nonetheless, everyone at the Mudd Club hated everything that had to do with Studio 54.

AB: Some of your images are from the roller disco.

BB: In New York there were a lot ofreally good roller skaters who used to party and perform their tricks together. Mostly I was at the Brooklyn Empire Roller Disco a lot, where African- Americans in particular came to skate. There was a mood of friendly competition, the air was sweaty, the audience full of energy.

AB: Did you feel a part ofthe scene then, or more like a kind ofobserver?

BB: I was a journalist, observing, taking notes. I still felt accepted. What attracted me the first night was just a feeling of being free to express yourself the way you wanted. There was a kind of belongingness I’d never encountered before, nowhere else.

AB: And you’re from the Woodstock generation.

BB: Exactly. I thought we were very tolerant. But in fact, my generation was heavily influenced by doctrine. You always had to be anti-everything. Anti-establishment, anti-Vietnam, anti-war, anti-materialism, anti-short hair. The scene of the late seventies in New York City was open- minded in a totally different way. Everything unfolded in the brief period of time after Stonewall, i.e. in the clashes between the police and homo and transsexuals, and before the AIDS epidemic. It was about equality and sex, for a short time everything was possible.

AB: What made a photo special for you then?

BB: As a photographer you’re always looking out for the unusual. So do I. When I went to Studio 54 for the first time, there was a long line of paparazzi who were only interested in somehow shooting a star. Every movement was documented there. But I wasn’t into this wrestling match with the other photographers at all, I wasn’t interested in photographing how Andy Warhol was sitting on the couch with Mick Jagger. If anything, as a portrait photographer, I wanted to have Mick Jagger sitting in my studio, with real light and decent equipment, interacting with him personally. In the clubs, I was much more interested in the other people who, in turn, wanted to celebrate the celebrities because they brought the vibe with them. So I only focused on what was going on alongside the stars and in particular in the underground clubs.

AB: Which makes your photographs fundamentally different from other images from this time. Do you look back nostalgically on those years from 1977–79, or you don’t miss it?

BB: If hadn’t been there, I would probably regret it. But I don’t want to go back; I think our culture has evolved in extremely significant ways since then. Because even ifgay, heterosexual, and transsexuals were happily dancing side by side on the dance floor, and women and blacks weren’t discriminated against there, this equality ended pretty quickly as soon as the clubs locked their doors. Discrimination and racism still ruled the streets; equal rights were never part of the equation then. I think, in general, the world is a better place today, even though there seem to be current movements trying to ratchet everything back a bit, but that will pass. I believe people really want a world of belongingness, tolerance, and acceptance.

When co-curator Arman Naféei encountered the photographs of Bill Bernstein at the Museum of Sex in New York in 2018, he quickly realized their particular value as testaments to a particular period in time.

Together with gallery owner Kirsten Landwehr, who has been acquainted with the work ofthe American photographer for several years, he decided to honor Bernstein’s wish for an exhibition in Berlin. Bernstein’s series The Bill Amber Photographs—NYC 1977 to 1979 will be on view at the Galerie für Moderne Fotografie in Berlin-Mitte starting September 27. The opening will be held on September 26 at the Galerie für Moderne Fotografie and followed by a reception at the 25hours Hotel Bikini Berlin of the 25hours Hotels Group, which has already included thirty of Bernstein’s works in their collection. On this evening, at the legendary Monkey Bar, various DJs, including Nicky Siano and Arman Nafeei, will pay tribute to the photographer by bringing disco fever back to life with new and old hits.

Text: Anneli Botz