Anders Edström’s Moments Between Moments

For a number of years, beginning around 1993, Anders Edström was something like the house photographer at Purple magazine (where I’m still a writer). Olivier Zahm, one of the creators of Purple (with Elein Fleiss), had met Anders when Anders was taking pictures for designer Martin Margiela. What Olivier noticed was the way Anders stood, one arm akimbo, the other clamping the camera to his eye, hips back, one leg forward, elegant as a fencer, but unassuming in his approach. Anders is quiet in his manner but confident in his ability. Somehow Olivier noticed all of that, and after seeing his photographs he got Anders to shoot for the Purple. His style and attitude matched the magazine’s sensibility.

Recently he related to me in an email: “What I hate about fashion shoots is having to interact with people I don’t know. That always makes me nervous, because I’m forced to feel aggressive, pointing a camera. That’s also one of the reasons I take so few pictures [which terrifies art directors]. What interests me about photography isn’t so much the act of taking pictures so much as the selection of what to shoot.” He likes, Anders continued, “diluted pictures, pictures full of light, moments between moments, pictures that are free of classical composition, pictures that can be seen quickly, and that don’t seem to leave a strong impression but that slowly seep into the mind.”

Pictures that focus on “between moments.”

Anders is one of the best I know of at capturing the light between things. Light is a photographer’s medium; it’s the soul of photography, so to speak, and, on a grander scheme, light is the very ego of life, the source of vision, eroticism, idea, and imagination. Anders engages light’s materiality — the organic

For a number of years, beginning around 1993, Anders Edström was something like the house photographer at Purple magazine (where I’m still a writer). Olivier Zahm, one of the creators of Purple (with Elein Fleiss), had met Anders when Anders was taking pictures for designer Martin Margiela. What Olivier noticed was the way Anders stood, one arm akimbo, the other clamping the camera to his eye, hips back, one leg forward, elegant as a fencer, but unassuming in his approach. Anders is quiet in his manner but confident in his ability. Somehow Olivier noticed all of that, and after seeing his photographs he got Anders to shoot for the Purple. His style and attitude matched the magazine’s sensibility.

Recently he related to me in an email: “What I hate about fashion shoots is having to interact with people I don’t know. That always makes me nervous, because I’m forced to feel aggressive, pointing a camera. That’s also one of the reasons I take so few pictures [which terrifies art directors]. What interests me about photography isn’t so much the act of taking pictures so much as the selection of what to shoot.” He likes, Anders continued, “diluted pictures, pictures full of light, moments between moments, pictures that are free of classical composition, pictures that can be seen quickly, and that don’t seem to leave a strong impression but that slowly seep into the mind.”

Pictures that focus on “between moments.”

Anders is one of the best I know of at capturing the light between things. Light is a photographer’s medium; it’s the soul of photography, so to speak, and, on a grander scheme, light is the very ego of life, the source of vision, eroticism, idea, and imagination. Anders engages light’s materiality — the organic

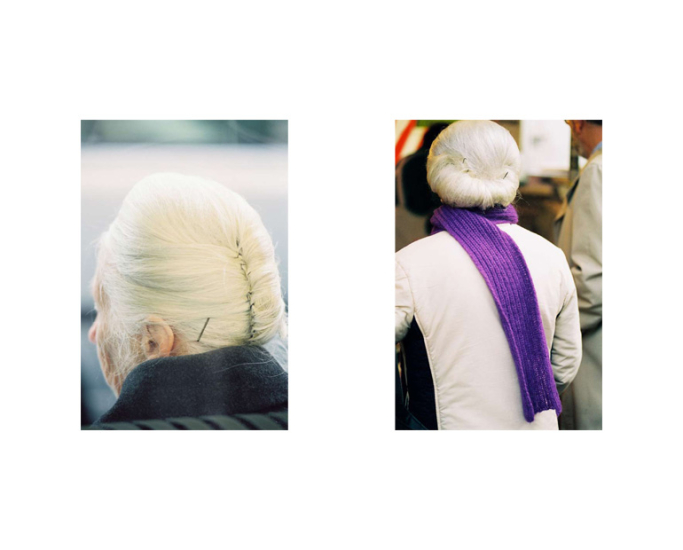

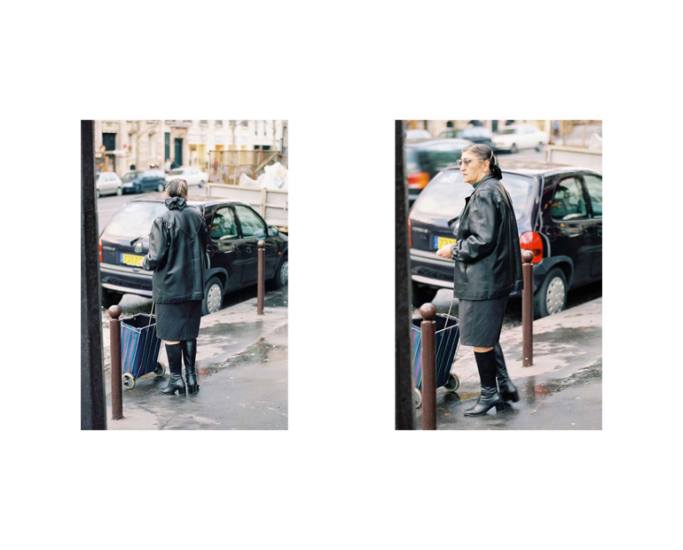

eroticism of light in an almost religious sense, capturing its aural essence, as light illuminates and gives shape to things and situations. Most of his subjects are shot casually, often close to home. Many are people he knows, including his family, which allows him some kind of unobtrusive freedom to focus on the “betweenness” he speaks of. He photographs parks, birds, cityscapes, rivers, lakes, landscapes, spiders, blobs of paint, assorted objects, unusual details, such as a close-up of light illuminating an ear, which is one of my favorite of his images. He captures normal, seemingly uneventful situations, focusing on the light as the dramatic ingredient, shying away from the theatrical glamour of people or situations. The light in his pictures always has a material presence.

Many of the fashion shoots he’s done for Purple were of girls in everyday situations, all seemingly natural, even when the shoots were carefully organized beforehand. The passers-by in his series, “Dimanche,” were photographed unaware. They might be thought of as fashion’s anti-aesthetic: elderly people in a Sunday-like situation — a day of self-reflection, to pause and recollection, to self-indulge or to spend unfashionably with family or friends. The point was to show how style is a form of humanism, and not an expression of exclusion or elitism. Rather, he wanted to capture personal aspects of taste more on the lines of self-awareness or social pride, people who take care of their public personae without exaggerating it, and, as such, can be noticed, at least by people like Anders, for their unpretentious individuality.

In an essay I published in 1999, titled “Paranoia Soft,”* I tried to describe the kind of pictures Anders takes. He was, I felt, an exemplar of a style of photography then “in the air,” such as by Camille Vivier, Wolfgang Tillmans, Mark Borthwick, and Terry

Many of the fashion shoots he’s done for Purple were of girls in everyday situations, all seemingly natural, even when the shoots were carefully organized beforehand. The passers-by in his series, “Dimanche,” were photographed unaware. They might be thought of as fashion’s anti-aesthetic: elderly people in a Sunday-like situation — a day of self-reflection, to pause and recollection, to self-indulge or to spend unfashionably with family or friends. The point was to show how style is a form of humanism, and not an expression of exclusion or elitism. Rather, he wanted to capture personal aspects of taste more on the lines of self-awareness or social pride, people who take care of their public personae without exaggerating it, and, as such, can be noticed, at least by people like Anders, for their unpretentious individuality.

In an essay I published in 1999, titled “Paranoia Soft,”* I tried to describe the kind of pictures Anders takes. He was, I felt, an exemplar of a style of photography then “in the air,” such as by Camille Vivier, Wolfgang Tillmans, Mark Borthwick, and Terry

Richardson. By “soft” paranoia I didn’t mean conspiracy theories, but a wariness of mass-market media and the commercialization of art — and of life. I described his style of photography as a “look” that had been “refracted through home movies and faded pictures and photo albums,” whose subjects were “more real, more present, and more actuel,” and not like the aggressive images commonly seen in glossy fashion magazines and expensive Hollywood movies. I compared this international style of photography to independent films that had been emerging in Asia, such as Takashi Kitano’s Sonatine (1993) and Hana-bi (1997), and from Western filmmakers like Larry Clark’s Kids (1995) and Lars Von Trier’s Breaking the Waves (1996) and The Idiots (1997).

We were all heavily influenced by cinema. Who isn’t? Like these cinematographers, and like Purple magazine, a feeling of commercial wariness, so common in a world saturated with ads and exaggeration, was shared among us. Beyond that, however, we were, and are all (certainly anyone reading this is), products of a Common People’s aesthetic that exists today, in the electronic age, where we descendants of Karl Marx’s proletariat are now independent spirits, casual dressers, and connected to the World Wide Web’s evolutionary awareness, dependent on a computer and an email address. Even so, Anders hasn’t gone digital entirely, he still only shoots with a very good 35mm camera — but not one beyond a computer owner’s price bracket. And he continues to presents his very empathetic humanism, which he makes vivid in an aesthetic of “betweenness” and in the fullness and enveloping radiance of light. by Jeff Rian

We were all heavily influenced by cinema. Who isn’t? Like these cinematographers, and like Purple magazine, a feeling of commercial wariness, so common in a world saturated with ads and exaggeration, was shared among us. Beyond that, however, we were, and are all (certainly anyone reading this is), products of a Common People’s aesthetic that exists today, in the electronic age, where we descendants of Karl Marx’s proletariat are now independent spirits, casual dressers, and connected to the World Wide Web’s evolutionary awareness, dependent on a computer and an email address. Even so, Anders hasn’t gone digital entirely, he still only shoots with a very good 35mm camera — but not one beyond a computer owner’s price bracket. And he continues to presents his very empathetic humanism, which he makes vivid in an aesthetic of “betweenness” and in the fullness and enveloping radiance of light. by Jeff Rian